North-East India: Development and Conservation

Newsletter

Subscribe now to get notified about IU Nagaland Journal updates!

Search

North-East India: Development and Conservation

Dr. Gunjan Kumar

Assistant Professor

Department of Economics

Jananayak Chandrashekhar University

Ballia, Uttar Pradesh

Abstract

There is a challenge of conserving the nature and environment of North-East India without compromising its economic development. The urban based exogenous development strategy with focus on industrialization may not benefit the region and perhaps may hinder the way of becoming the region self-sufficient. Development model in the region must analyse the possible cooperation and contradictions that are emerging between environment and development factors here. The paper suggests Bioregional model as most fit model for the region and discusses the economic diversification of this region (NER) which can take many forms. The mixture of local identity and place-based knowledge can play a central role in the formation of several rural businesses in the region.

Keywords

North-East Region, Development, Bioregional, Local,

Introduction

There is an ongoing subject of argument in academics whether a specific environment (such as rural, hilly, remote etc.) embodies a hindrance or bids opportunities to be recognized and appreciated (Newbery et al., 2017). Undoubtedly, the remoteness or accessibility of a location matters for general development (entrepreneurship).Nevertheless, the existence of important natural resources, the climate, heritage, and the landscape present opportunities (Stathopoulou, S., 2004). Many literatures (Basumatary, M. and Panda, B., 2020; Mishra, S.K., 1999; Ray, B. D. and Baishya, P., 1998; Rao, V. V., 1975) talk about the natural and geographical constraints of Northeast India. Nevertheless, Northeast India is known for its spatial diversity and mesmerizing beauty. Its green land, geographical and natural multiplicity sets the Northeast quite dissimilar from other parts of the country.Three states from the northeast region are among the top five states of India in terms of the highest forest cover percentage of their geographical area.According to the India State of Forest Report (2021), northeastern states' total forest cover area is 64.66% of their total geographical area, which is about 1,69,521 sq km. A country always needs such green zones and the integrated geographical, agricultural, and environmental systems for sustainability (Van der Ploeg et al., 2000). While there is a 1,540 sq.km (+0.22%) increase in the forest cover of India over 2019, the region experienced a loss of 1,020 sq. km forest cover between 2019 and 2021.Hence, there is a challenge of conserving the nature and environment of North-East India without compromising its economic development.

In the global investors summit, 2023,the government has showcased the investment and trade potential of India’s Northeast Region as well as the scope for industrial growth and expansion in the region. Industrial activities can be a possible solution for the economic lag of the region. However, the overall contribution of industrialization in terms of employment, especially in terms of local employment, is highly debated (Deller, S. et al., 2019). Industrial activities, which are generally motivated by profit and mobility, are mostly found engaging with a spatial context merely as a location for their immediate activities (Korsgaard, S. et al., 2015). There are less concerns about the environment and development of the region. There are evidences of exploitation of natural resources and shutdown of industries once the incentives, scheme, and subsidies in the regions end. Uttarakh and is one such example. Chand, R.et al. (2017) mentioned that the non-agricultural sector, mainly manufacturing, which shifted to the rural areas, could not bring significant employment gains or reduction in disparity in rural India. Further, potential tensions are also embedded in any such development drive: Who will be the major beneficiary of this new development? Will it be investors, grassroots farmers, or the population who have conserved the environment so far? (Van der Ploeg et al., 2000).The urban based development with focus on industrialization may not benefit the region satisfactorily. Hence, this is becoming an ever more serious question: how should the northeast economy deal with the challenges of continued peripherality, low income, and less economic activities?

The intent of the paper is to raise the question: Do the region really need the rapid growth in the manner that other regions achieved? It should not necessarily be the ambition. Rather, the focus should be on enhancement of the quality of the place and life of the people and enhancement of the value of localized resources. The social and cultural recognition of urbanity and industrialization on the upper hand and rurality as a negative trait (Shahraki, H. and Heydari, E., 2019) needs to be changed. Korsgaard, S. et al. (2015) mentioned a place more than a simple location; it is constituted by the practices that take place in a location. Korsgaard, S. et al. (2015)mentioned a place more than just a physical site or a piece of land; it is shaped by the activities that occur within that territory. It is the part where people are directly linked with natural resources to earn livelihood (the way to make a living) and lifestyles there balance the regional problems (Tejaram, N., 2017; Siemens, 2014).The people of northeastern states and their lives are full of colours, which is clearly reflected in the festivals and celebrations observed there. Different people of this region celebrate festivals in different ways revolving around their varied livelihoods and ways of living with a large fanfare round the year. Therefore, the development of the region should be in its own way and as per its environmental and geographical climate.

North-East Region

The northeastern part of India, popularly known as the North Eastern Region (NER), is the easternmost part of India and is made up of the state of Sikkim, also known as the "brother state of the seven sisters", and the eight states known as the "Seven Sisters": Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Tripura. Nearly 99 percent of its total geographical boundary (5,182 kilometers) is in the form of international border shared by the region with a number of neighboring countries: 1,395 kilometers to the north with China, 1,640 kilometers to the east with Myanmar, 1,596 kilometers to the south-west with Bangladesh, 97 kilometers to the west with Nepal, and 455 kilometers to the north-west with Bhutan. NER has an area of about 262,184 square kilometers, which is almost 8 percent of India’s geographical area. It is among Asia's most linguistically and ethnically diverse regions. Every state has its own unique features, distinct culture, traditions, and practices. With its picturesque hills, verdant meadows, and innumerable species of flora and fauna, each state is like a traveler's dream come true.

A narrow 20-kilometer-wide land corridor that connects it to the rest of India makes the Northeast a true frontier region. The Siliguri Corridor connects the region to the rest of mainland India. Geographically, with the exception of the Brahmaputra, Barak, and Imphal valleys, as well as a few flatlands situated between the Meghalayan and Tripuran hills, the remaining two-thirds of the region is hilly, with valleys and plains scattered throughout. The elevation ranges from nearly sea level to more than 7,000 meters (23,000 feet) above mean sea level.

Development Strategy

There is an assumption that the economic growth in the mountainous rural areas is exogenous by attracting capital from other areas or most popularly through industrial attraction efforts or relocating firms through various financial incentives (Deller, S. et al., 2019; Lowe, P. et al., 2019).But this exogenous development strategy is against making regions self-sufficient. The declining efficacy of industrial provision and failure of other rural development strategies have driven a gradual transition to endogenous initiatives that capitalize on local resources, skills, and knowledge. (Deller, S. et al., 2019). Therefore, there should be a development approach that if not isolated, at least less dependent on external forces.

The key to the development in the region is the local participation and locally established economic opportunities (Dzvimbo, M. A.et. al., 2017; Lopez, M.,2019).The development model in the region must analyze the possible cooperation and contradictions that are emerging between environment and development factors. The most fit model for the region may be the Bioregional model. This model acclaims subsistence regions with flexible production systems and production based on local needs, small enterprises, and decentralized management. Lowe, P. (2019) coined the term “Vernacular Expertise” related to it ‘an expertise that is place-based, place-generated and place-focused’. The LEADER (Liaison Entre Actions de Development de Rurale) programme of the European Union is one of such examples to learn from, which provides funding for area-based local strategies to induce regional development (Martin, P., 2013).

But, to implement such development programs, there is a requirement for finance at workable scale rather than micro loans; there is a need for fostering job-creating entrepreneurship rather than subsistence livelihoods (Basole, A. and Chandy, V., 2019).While the northeast communities need financial services the most, they remain the largest unreserved market for financial services. In the year 2021, the credit-deposit ratio of regional rural banks in the North-Eastern region was only 38.3 percent in comparison to 71.4 percent at the all-India level (RBI, 2021). Ensuring the financial inclusion of northeast communities can unlock considerable economic potential of the area.

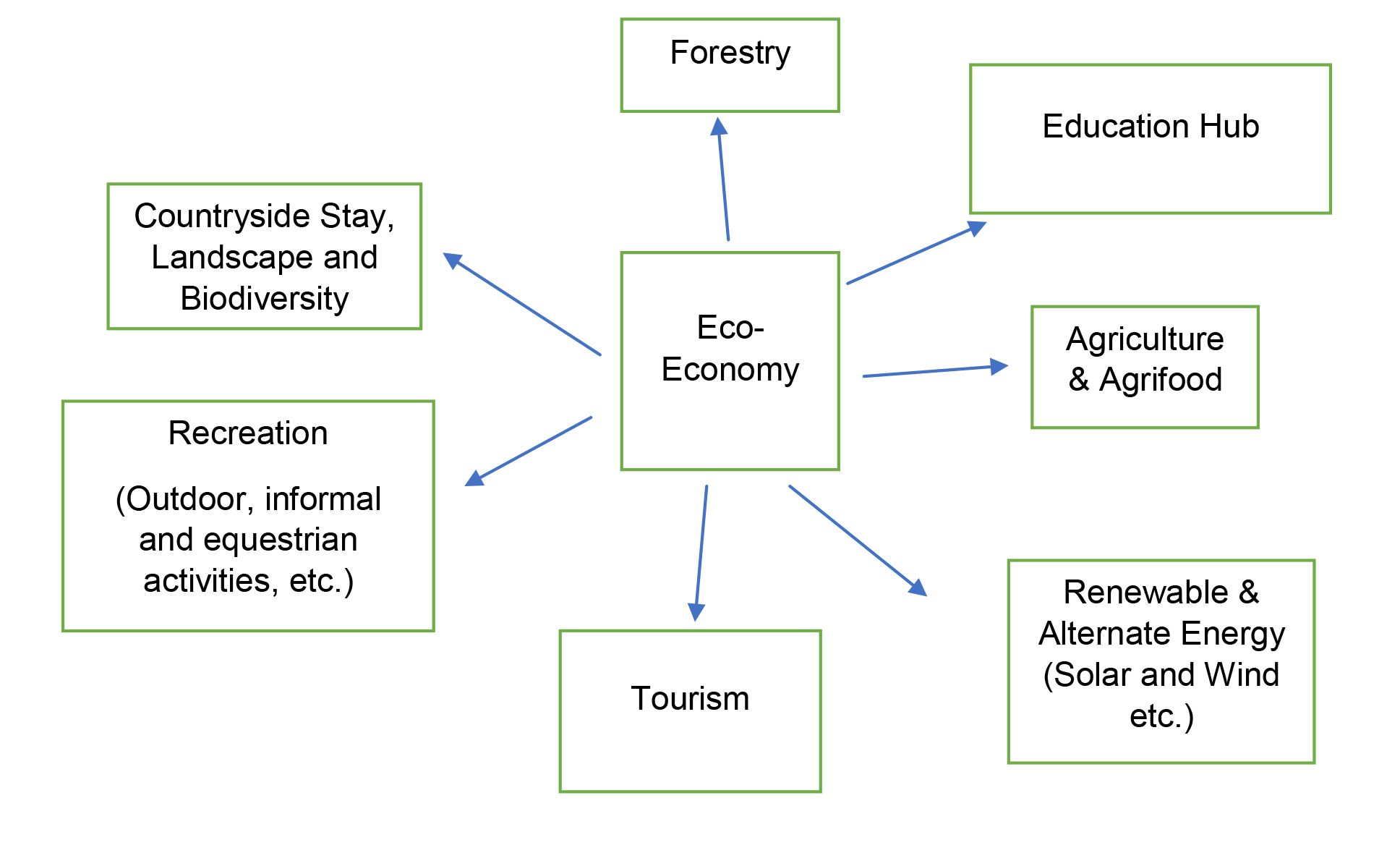

Economic diversification in this region (NER) can take many forms, including retailing (e.g., organic farm shops, craft centres, food processing, etc.), sports and recreation (e.g., outdoor, informal, water-based and equestrian activities), services (workshops, education), green energy hubs, and tourism (see figure 1). There is a need to see the region and its assets as active agents rather than passive beneficiaries of government policies (Lowe P. and Ward, N., 2007). The combination of place-based knowledge and skills with local identity can play a vital role in the development of rural businesses.It is essential that this pluri-activity be considered as a crucial component of regional development. The requirement is to engage with the environment of the place and create value using local resources for the upliftment of the rural economy. Development in the region should be multifaceted-managing landscapes, preserving natural values, agritourism, organic farming, and producing high-quality, locally relevant goods. Small labour-intensive manufacturing rather than large ones can play important role in employment generation (Dutta, S., 2020).

Figure 1: Bio-regional / Eco-economy Model

Northeastern states provide scope for activities like fishing, boating, rafting, trekking, and hiking. Furthermore, there are several national parks and wildlife sanctuaries with uncommon animals, birds, and plants that will undoubtedly give tourists and researchers interesting and new information. It is recommended to make the region attractive, focus on identifying local and regional assets, move towards the work with people approach which respects the primacy of the people, to guarantee social well-being and sustainable development (Lopez, M. et al., 2019).There should be promotion of distinct territorial, local, and/or regional quality food or other products. There is a need to commoditise local culture, local breeds, varieties and revalorise place through its cultural identity for the development of entrepreneurship and innovation (Stathopoulou, S., 2004). To conserve the environment and identity of the region, we need to contemplate the development in the region with community participation, locally established economic opportunities, and reinforcement of regional identity. The initiatives from within the society and region may be sustainable and more beneficial for the region. Without economic vitality, other factors that make living attractive, such as health, social services, education, housing, or transport facilities cannot be developed and sustained in the long run.

References

Basole, A., & Chandy, V. (2019). Microenterprises in India: a multidimensional analysis. Project Report, Azim Premji University and Global Alliance for Mass Entrepreneurship, Bengaluru. http://publications.azimpremjifoundation.org/id/eprint/2115.

Basumatary, N., & Panda, B. (2020). A review of institutional and developmental issues in North-East India. Indian Journal of Public Administration, 66(2), 206-218.

Chand, R., Srivastava, S. K., & Singh, J. (2017). Changing structure of rural economy of India implications for employment and growth. New Delhi: NITI Aayog.

Deller, S., Kures, M., & Conroy, T. (2019). Rural entrepreneurship and migration. Journal of Rural Studies, 66, 30-42.

Dutta, S. (2020). Development of the rural small manufacturing sector in Gujarat and West Bengal: a comparative study. Development in Practice, 30(2), 154-167.

Dzvimbo, M. A., Monga, M., &Mashizha, T. M. (2017). The link between rural institutions and rural development: Reflections on smallholder farmers and donors in Zimbabwe. Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 22(6), 46-53.

Gkartzios, M., & Lowe, P. (2019). Revisiting neo-endogenous rural development. The Routledge companion to rural planning, 159-169.

India State of Forest Report (ISFR), 2021.

Korsgaard, S., Müller, S., & Tanvig, H. W. (2015). Rural entrepreneurship or entrepreneurship in the rural–between place and space. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. DOI: 10.1108/IJEBR-11-2013-0205.

López, M., Cazorla, A., & Panta, M. D. P. (2019). Rural Entrepreneurship Strategies: Empirical Experience in the Northern Sub-Plateau of Spain. Sustainability, 11(5), 1243.

Lowe, P., Phillipson, J., Proctor, A., &Gkartzios, M. (2019). Expertise in rural development: A conceptual and empirical analysis. World Development, 116, 28-37.

Lowe, P., & Ward, N. (2007). Sustainable rural economies: some lessons from the English experience. Sustainable Development, 15(5), 307-317.

Petrick, M. (2013). Reversing the rural race to the bottom: an evolutionary model of neo-endogenous rural development. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 40(4), 707-735.

Mishra, S. K. (1999). Rural development in the North-Eastern Region of India: Constraints and prospects.Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/1833/MPRA Paper No. 1833.

Mueller, S., & Korsgaard, S. (2014). (Re) Sources of opportunities–The role of spatial context for entrepreneurship. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2014, No. 1, p. 13468). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

Netar, Tejaram (2017): Impact of Institutions on Rural Livelihoods Case Study of Village Mundoti.MPRA_paper_87287.pdf.https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/id/eprint/87287.

Newbery, R., Siwale, J., & Henley, A. (2017). Rural entrepreneurship theory in the developing and developed world. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 18(1), 3-4.

Rao, V. V. (1975). North East India: Problems and Prospects. The Indian Journal of Political Science, 36(1), 1-12.

Ray, B. D., & Baishya, P. (1998). Sociological constraints to industrial development in North East India.Industrial DevelopmentEconomic DevelopmentEntrepreneurshipNorth-East India,New Delhi: Concept Publishing.

Shahraki, H., & Heydari, E. (2019). Rethinking rural entrepreneurship in the era of globalization: some observations from Iran. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 42.

Siemens, L. (2014). “We moved here for the lifestyle”: A picture of entrepreneurship in rural British Columbia. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 27(2), 121-142.

Stathopoulou, S., Psaltopoulos, D., & Skuras, D. (2004). Rural entrepreneurship in Europe. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 10 (6), 404-425.

Van der Ploeg, J. D., Renting, H., Brunori, G., Knickel, K., Mannion, J., Marsden, T., ... & Ventura, F. (2000). Rural development: from practices and policies towards theory. Sociologiaruralis, 40(4), 391-408.